– Jerome K. Jerome

English Lesson

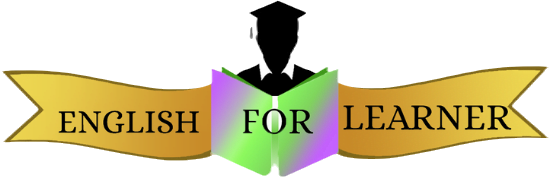

The neighbourhood of Streatley and Goring is a great fishing centre. The river abounds in pike, roach, dace, gudgeon and eels, and you can sit and fish for them all day. Some people do. They never catch them. I never knew anybody who caught anything up the Thames, except minnows and dead cats, but that has nothing to do with fishing!

I am not a good fisherman myself. I devoted a considerable amount of attention to the subject at one time, but the old hands told me that I would never be really good at it. They said that I was an extremely neat thrower; I have plenty of gumption and quite enough constitutional laziness. To gain any position as a Thames angler, I would require more imagination and more power of invention. Some people are under the impression that all that is required to make a good fisherman is the ability to tell lies easily

I knew a young man who had determined never to exaggerate his hauls by more than twenty-five per cent. “When I have caught forty fish, I will tell that I have caught fifty. But I will not lie any more than that, because it is sinful to lie,” he said. But this plan did not work well as the greatest number of fish he ever caught in one day was three, and you can’t add twenty-five per cent to three — at least, not in fish. So, to simplify matters, he would just double the quantity.

He stuck to this arrangement for a couple of months, and then he grew dissatisfied. When he had caught three small fish and said he had caught six, it used to make him quite jealous to hear a man, whom he knew for a fact had only caught one, going about telling people he had landed two dozen. Eventually, he made one final arrangement and that was to count each fish that he caught as ten, and to assume ten to begin with. For example, if he did not catch any fish at all, then he said he had caught ten — you could never catch less than ten fish by his system; that was the foundation of it. Then, if by any chance he really did catch

one fish, he called it twenty, while two fish would count thirty and so on.

One day, George and I went to a parlour and began chatting with an old fellow there. Then a pause ensued in the conversation, during which our eyes rested upon a dusty old glass _ case, fixed high up above the chimney-piece and containing a trout.

Ah!” said the old gentleman, following the direction of my gaze, “fine fellow that, ain’t he?” George asked the old man how much he thought it weighed.

“Eighteen pounds six ounces,” he said. He continued, “I caught him just below the bridge with a minnow. You don’t see many fish that size about here now.

And out he went, and left us alone.

We were still looking at the trout when the local carrier, who had just stopped at the parlour, also looked at the fish.

“Good-sized trout,” said George, turning around to him.

‘Maybe you weren’t here, sir, when that fish was caught?” asked the man.

“No,” we told him. We were strangers in the neighbourhood.

“Ah!” said the carrier, “It was nearly five years ago that I caught that trout.

“Oh! Was it you who caught it, then?” said I.

“Yes, sir,” he replied. “I caught him just below the lock — leastways. Well, you see, he weighed

twenty-six pounds. Good night, gentlemen.

Five minutes afterwards, a third man came in, and described how he had bleakly caught it early one morning; and then he left, and a stolid, solemn-looking, middle-aged individual came in and sat down over by the window.

None of us spoke for a while; but George turned to the new comer and said, “Would you tell us how you caught that trout up there?”

“Who told you I caught that trout?” was the surprised query

We said that nobody had told us so, but somehow, we felt instinctively that it was he who had done it.

And then he went on and told us how it had taken him half an hour to land it, and how it had broken his rod. He said that it had weighed thirty-four pounds.

When he was gone, the landlord came in to us. We told him the various histories we had heard about his trout, and we all laughed very heartily.

And then he told us the real history of the fish. It seemed that he had caught it when he was quite a lad.

At this point, he was called out of the room, and we again turned our gaze upon the fish. The more we looked at it, the more we marvelled at it.

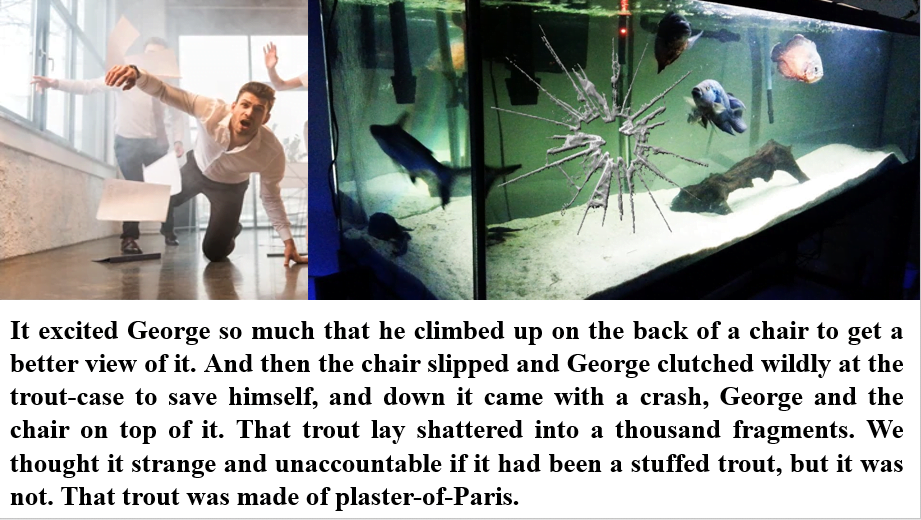

It excited George so much that he climbed up on the back of a chair to get a better view of it. And then the chair slipped and George clutched wildly at the trout-case to save himself, and down it came with a crash, George and the chair on top of it.

That trout lay shattered into a thousand fragments. We thought it strange and unaccountable if it had been a stuffed trout, but it was not.

That trout was made of plaster-of-Paris.